I’ve been to Tokyo twice. Most people know about the wild public transport issues they have on the subway – the harassment, the people whose job it is to shove as meany people as possible into a single train car, etc. Having been on a Tokyo subway during rush hour… It’s a nightmare for someone that’s worried about misunderstandings. Sometimes I got crammed between two or more very polite Japanese women and have no choice but to smell their hair. (I’m roughly four inches taller than the average Japanese woman, so my nose is right at scalp height when standing straight up)

Where am I going with this? I have a very specific issue with a single scene in Signs Preceding the End of the World. I’m sure I’m taking this too seriously, but there’s a part in the book where a coyote is helping Makina across a river on her way to Texas, and the narrative goes out of it’s way to show that he appears disinterested in her, which is interesting since every other male character so far seems ready to jump her bones with a second’s notice. Yet, while they’re rowing across, Makina notices him smell her hair. Just thinking about this…. If she’s on a back stroke while he’s on a front stroke with the oars, wouldn’t he be more or less forced to inhale while she was leaning back (depending on his breathing rhythm)?

Now I’ve polled a few people that I assume are female, and they’ve informed me that this kind of thing isn’t uncommon, it is very noticeable, and it is “totally gross,” but I really don’t know what to think of it. Did he do it on purpose? Why? Did he like what Makina smelled like? Does it matter?

I can’t even begin to answer these questions because I can’t even fathom why someone would smell another person’s hair. I think I’ve only ever done it on purpose when my girlfriend asked me if I liked the new conditioner she got. It was pretty good, kind of like a melon smell but better because it was coming from a woman I love.

I guess my point is that there are certain aspects of the novel that I can’t even begin to understand, principally the female experience. I’ve been to gay bars and been objectified and hit on in ways that made me super uncomfortable and had people touch me without my consent, I’ve had coworkers at work make weird advances on me or hit on me or touch me, but as a man it’s a much different experience with different types of weirdness and different feelings of conflict. And even when it’s directly happening to me, I’m not really “tuned in” to it like Makina is in the novel.

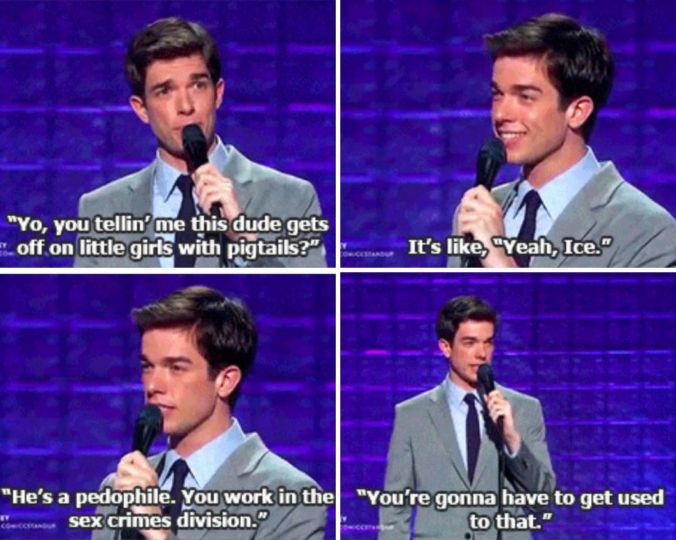

I’ll end with this: is it even worthwhile for someone like me to try to understand this aspect of the novel? Or will I always be fumbling trying to deconstruct an alien experience from a perspective totally divorced from my own ego? I’ve always felt constrained in these respects as a man, and I want to understand these aspects of life in a way that doesn’t make me feel like Ice T on Law and Order SVU.