You must have read a couple of novels, epics, and plays during your academic career that was first intended for an audience of a different language. These works of art were then translated to the English we are familiar with. However, somebody had to translate the piece of literature, correct? This brings into question the translator themselves: is the translation ‘authentic’ or did the translator add in a ‘bit’ of themselves while translating certain passages or even pages?

This dilemma regarding translation is the main focus in 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei by Elliot Weinberger & Octavio Paz. Weinberger & Paz explore 19 (and an extra 10 in the afterwords) translations various authors transcribed about a single Chinese poem throughout history. The poem was created before the 17th century by Wang Wei, revered as a “master of poems” at the peak of the Tang Dynasty in China. You can only imagine the pressure the authors felt in giving this respected poet the justice it deserved in their translations.

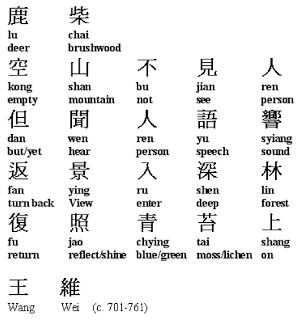

What makes the poem, “Lu Zhai” or “Deer Park”, very tedious to translate is the fundamental issue of differing alphabets the Chinese and the English language have. In the classical Chinese, a character signifies a word of a single syllable as seen above. Therefore, when reading in classical Chinese, the grammar and vocabulary we know in English can be defined in a few Chinese characters or pictographs. As a result, the translating authors feel as though they are playing a “… game of pretending to read Chinese,” (pg 3) by attempting to choose the most ‘appropriate’ word in English to represent the Chinese character.

You may ask yourself now, “Why does any of this matter? They are only words and a single or couple of substituted words shouldn’t make a big difference.” If that was the case, there wouldn’t even be 19 (plus 10) different translations about a single Chinese quatrain. Since classic Chinese characters ‘pack’ a lot of meaning in a single ‘word’, the responsibility lays on the translator to a.) literally attempt to transcribe the work to the English alphabet then to common English words or b.) make a few adjustments with an added context in order to bring out its true “essence.” As a result, the readers will obtain a different reading experience when reading different translations coming from different authors. Therefore, we gain an array of perspectives and concepts throughout each of the translations made.

So what makes a translated work ‘authentic’? Well, unless you have a lot of time on your hands to set out in learning a complete language, then there might really be no ‘correct’ answer. Heck, when we read a novel in English, we always come across something ‘new’ we missed on the first or third time we read the work. Not every reading experience is always the same. The final answer is up to you, the reader. If you don’t like a certain work’s translation, then go on to the next one with a different translator. Give your gratitude to the translators for making switching possible. Or we would really need to set a chunk of our time aside to learn a variety of languages.